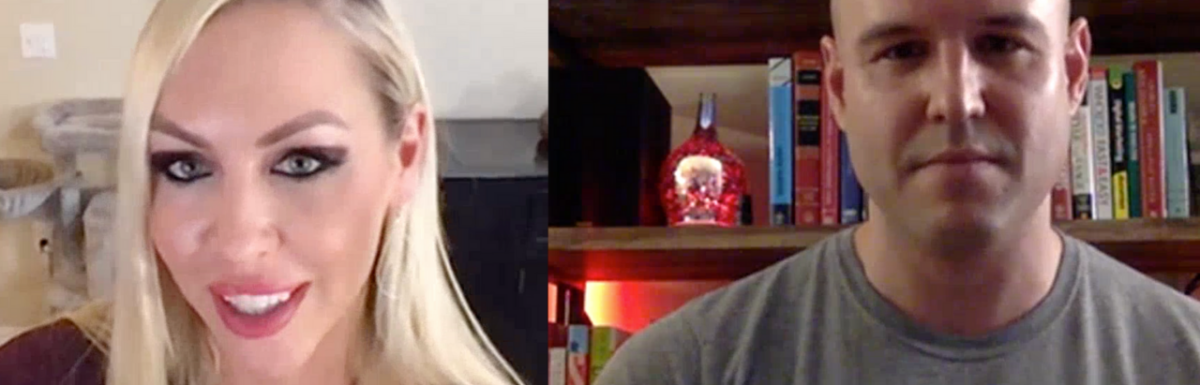

Synopsis: Chris Scott interviews Briana Theroux, a Mind-Body Nutrition Coach certified by the Institute for the Psychology of Eating as well as the newest Fit Recovery Coach. Briana lives an alcohol-free lifestyle and has extensive experience with compulsive behavior, addictions, and nutritional strategies for optimizing physical and mental health.

Here are the main topics discussed in this episode:

- The biochemical aspect of addiction and recovery

- Why the biochemical and psychological aspect of addiction affect each other

- What about trauma? Why people can develop addictions without a history of trauma, and why trauma doesn’t equal addiction as an adult (although it significantly increases likelihood)

- How drinking regularly can lead to biochemical imbalances and mental health issues

- Why optimizing biochemical repair is almost always a much faster process than optimizing the psychological pillar

- A lot of people don’t know why they keep drinking even though they want to quit

- Case studies of people that have been alcohol-free and done some healing then drank again and realized alcohol is no longer pleasurable to them

- How binge eaters can reduce fear

- Compulsiveness

- Dopamine is a motivational neurochemical

- Rewiring your brain until normal little things give you pleasure (eg cooking dinner, going for a walk, hanging out with friends, reading a good book, etc.)

Resources mentioned in this episode:

Right-click here and save as to download this episode on your computer.

Speaker 1 (00:00): It's the ritual of going and getting it. And that is the dopamine hit. It's not even necessarily the use of the drug that heightens their dopamine. It's the behavior of going and getting it and accomplishing it. When I quit drinking and doing any kind of substances. What I started doing is I started writing that hit my dopamine pathway, just as good as anything else, because I get a reward from figuring stuff out and publishing it. It takes a while to get accustomed, to not like seeking out something that is giving you that high of a high, right. You need to resensitize your brain. So to speak.

Speaker 2 (00:45): Thanks for tuning in to the elevation recovery podcast you have for addiction, recovery strategies hosted by Chris Scott. Hey everyone. Welcome to the elevation recovery podcast. I'm Chris Scott. And today we have Vajrayana thorough as our guests. Um, Brianna has recently joined the fit recovery team and is a coach. And I'm also, I don't know if I've even officially announced this, but we have some new courses coming out sometime in the next six months or something like that, uh, is making an awesome course as well, coaches, uh, Tana and Matt Finch. So Diana, thanks for being on the show. Thank you for having me. Absolutely. So I know you had put out a very interesting article and video on the psychology of drinking or of addiction. And, um, a lot of people were fans of that. We're getting really good traction on YouTube. So I urge anyone to check that out and you've listed a couple of reasons for people to drink.

Speaker 2 (01:52): And this is kind of a, this is something that I reflect on often. It's kind of like a chicken and egg thing with the biochemical pillar and the psychological pillar. So it seems like there's a spectrum. Some people like me, or like Claudia Christian, who was recently on the show to talk about the Sinclair method. We envisioned our addictions as if not exclusively than primarily biochemical. And of course there's a biochemical component for anyone who's dependent on a substance. But my reason for starting drinking was that I went to college, which is a pretty universal reason for starting drinking. It almost seems like, like, why did you start drinking? I had a therapist asked me that once. And I was like, that's the stupidest question I've ever heard? Like, have you ever been to a party? That's why I started drinking,

Speaker 1 (02:42): Like to fit in. Right,

Speaker 2 (02:43): Exactly. So do you see that kind of as a spectrum as well? Cause then you also have people who will have a horrible divorce and they, they went to college and they drank and they never got physically hooked, but for whatever reason something happened or something crept up on them, just the amount they were drinking, maybe they were escaping and there is a psychological layer. That's more pronounced for them.

Speaker 1 (03:06): Yeah. There's definitely always psychological layers, I think with any addictive habits. But I think that the biochemical part has to come first, um, because if our brain isn't functioning correctly, then we can't do the work psychologically to reframe thoughts, right. It's just going to be incredibly difficult. And that's where you get the terms like white knuckling, right. Is when your biochemistry is all messed up and you can't make rational decisions at all. And so I do think that the biochemical part has to come first and then you work on the psychological aspect. I don't think that you can separate them completely because then next time you go to a party, even if your blood sugars balanced, your neurochemicals are fine. If you want to fit in. And you told yourself that the only way to fit in is by drinking, then you're going to drink even in neuro chemistry spot,

Speaker 2 (04:03): Do you have false assumptions? Right. And you have to explore those proactive. You have to identify them.

Speaker 1 (04:09): Exactly. A lot of people look at, uh, drinking as like completely caused by other things. Things like trauma's a big one that I hear a lot, that they were traumatized at some point in their life. Um, and so that's why they drank. And that's not true because over 90% of people that have a history with PTSD 80 or 90%, I'd have to look at the numbers, uh, do not drink or use substances to manage their condition. So if it was completely causal, then every single person that was ever traumatized would use, and that's not what we see. So

Speaker 2 (04:45): That's a fantastic point. Yeah. And I remember when I was in the, the traditional detox center that I went to, I was told that I had to have trauma because I was a so called alcoholic with a permanent disease. And the drinking was just a symptom of my disease, which was caused by trauma. So we have to be nuanced in the way we talk. And, um, this is more of a note to self you've been incredibly nuanced. I often talk about the biochemistry of addiction and then I have some people say, well, what about trauma? I don't think it's, you know, it can be layered as you say, but for me, I'm sitting there in detox trying to figure out what trauma had caused my addiction and we had to write it down. So I made up a bunch of stuff. I mean, I didn't make it up out of thin air, but I wrote down things that had happened that had never really had any impact on me.

Speaker 2 (05:41): Um, I mean, we're talking about like, almost on the level of like someone took my pencil once when I was in second grade, I'm trying to find things like, yes, I had things happen. I, I have a hearing impairment that could help. That was it. And then that was, they were like, you, you have a hearing. I honestly, I never wore hearing AIDS. I have somehow learned to read lips and it has been a non-issue ever since then. Yeah. I can somehow talk on the phone. My brain has somehow compensated for the hearing loss. So if you were to step into my ears or have my ears for a day, it might be very confusing, but I've learned to adapt and deal with it. I probably miss some things, you know, if someone's behind me yelling my name, I might not hear it. Um, cause I do rely a bit on like peripheral lip reading and all that. But anyway, it's not, as I can tell you, it's not a source of major trauma that would necessarily end inevitably result in an alcohol addiction. So Right now, of course, for some people there is trauma though. And I have to, one of the big questions I still haven't fully resolved is are they w if, you know, when those types of people who have a divorce or something really traumatic or a rape, or if that horrible, violent crime, and then they develop an alcohol addiction that they never had, is, is there a change in their brain chemistry that could create a predisposition that wasn't there since birth?

Speaker 1 (07:07): Well, there could be a predisposition, but it is a choice though, if you pick up a substance to manage those feelings, right. Um, for reference, I've had severe trauma in my life. Uh, I was married to a very physically abusive man strangled me, uh, till I was almost dead, gave me concussions. Um, I did not drink during that time. And I had PTSD. I developed OCD. I did not drink, but through my divorce, I had freedom and I was socializing more. I rationalized it differently. And so that's when I had my drinking issue. It's because of the reasons that I was using. So I don't think that the neurochemical imbalances from trauma, like usually you have a higher state of like adrenaline. Um, I don't think that that has to be like mediated with alcohol. Will it make you more predisposed? Yeah. But you could do anything to manage things. It like, it doesn't have to be,

Speaker 2 (08:06): It's not an inevitability, it's not causal in the sense of being deterministic, you could have picked up opioids if there's reacted well to brain chemistry, or you could have developed some strange, you know, behavioral addiction where you're hoarding things, and maybe you get a different, uh, you know, uh, um, uh, what do they call that, uh, process, uh, addiction? So, you know,

Speaker 1 (08:29): Me went through my trauma. I definitely, I developed OCD. So I did, I was coping through behavioral things, but the problem with alcohol, when we look at it as the solution to trauma, is that it causes more neurological issues. So you're less likely to overcome and heal from the trauma.

Speaker 2 (08:49): Alcohol being such a damaging substance tends to create its own subset of psychological problems that are strictly attributable to the fact that someone starts drinking and becomes dependent on it. They become deficient and all these neurochemicals, their life suffers as a result because of the actions they make with an unbalanced brand. That's kind of how I see it too. I did have psychological problems for sure, but I had been drinking for 10 years and the vast majority of my psychological problems could have been traced to the results of drinking day in and day out or having my relapse periods and abstinence periods. Again, again, going through kindling, you know, not being the, the confident fit person identity that I really wanted to have, and that I, since regained, ever since quitting alcohol. And then once I realized I'd regained that it, the absurdity of, of a permanent spiritual disease began to be apparent to me. Yes. Yeah. So, you know, in your experience, um, do you find, you say that you like to deal with the, the biochemical part first? Um, how long does it take people to heal their biochemistry in your experience versus the psychological issues?

Speaker 1 (10:06): It's a lot quicker to fix biochemical imbalances then, uh, psychological, because psychological issues are from a lifetime of conditioning. And a lot of them come from before we're even aware of our psychological processes. By the time you're seven, you have a lot of your programming done for you by society and your parents, your conditioning on what to expect from the world at large. Right? And so it takes a lot of work to undo that. Um, that's why it's really important to fix the biochemical stuff first, because you're going to be able to grasp and work through that stuff a lot easier. I time it really depends on how much they were drinking before. Like some people, it takes like three months, some people six months, some people a year, right? Depending on their drinking history.

Speaker 2 (10:59): Yeah. I that's been my experience as well. I find that people tend to gain a certain degree of resilience or realize that they're more resilient than they thought once they start using supplements and targeted nutrients to repair their, their neurochemistry and really their brain, body system and integrate things like exercise, which maybe without those nutrients, they would not have gone to the energy in order to walk into the gym. So it's like these things which are, which are, um, somewhat behavioral, like, do I make time to work out? You know, you could approach that in a, in a therapy, in a strict therapy type session, you'd be like, well, what, what are the reasons that you don't work out? And it's like, it's a lot of it's biochemical. And you find that you actually do have that strength. And then you go on to prove that you have the self-efficacy to be who you want to be and do things that you want to do. And then your beliefs about yourself change. Um, and for me, you know, I'm, I certainly don't have the same level of background in psychology that you do. I, it was a series of books actually beginning with some of Tony Robbins books, which helped me realize, you know, how much control actually had over my thoughts, my assumptions, my values, all of the things that I just were kind of running an autopilot in the background,

Speaker 1 (12:12): We'll think about them until we consciously pay attention to them. Either a lot of people that drink don't know why they drank. They just drink because they say they either like it, or they're at the stage where they know they don't like it, but they're like, why do I keep doing this thing while there is reasons you have rationalized it somewhere? So is it bringing you more pleasure? Like that's, that's where you have to find out, uh, what is driving the use, right? Because I think fixing biochemistry, like, even if you do that, like, if you're put in a situation that is familiar, that you numbed out, then all those reasons will go in your head. And that's when people relapse usually like years after their, sometimes their biochemistry is still messed up, but sometimes it's not, and they still do that. And it's all the reasoning that's going on.

Speaker 2 (13:07): Right. I've actually heard from some people who, as odd as it sounds tried to relapse, uh, for no good reason most of the time. And then they found that alcohol simply didn't have the same effect that it used to. It didn't fill the, the, the, yes, the boy. Well, maybe there wasn't a board though. In other words, they're putting a puzzle piece onto a complete puzzle and they're kinda like, Ugh. And I actually got a text message from someone, a former client being like, you ruined alcohol for me. Like, isn't it. Because then you realize that you don't need to live the rest of your life with a phobia, uh, thinking you're so fragile that, that introducing a, a inanimate chemical into your body is going to ruin your entire existence. It might be in congruent with your identity. And so then it might be something worth addressing.

Speaker 2 (13:56): It might be a bad idea because it's extremely toxic and there's not a lot of good that comes from it. And the trade-off is pretty bad. I mean, at this point there are lots of, there are drugs that I would love to do. I'd like to make critters psilocybin. I would like to see what effect that has on my mood. You know, I'm not opposed to like THC or CBD tinctures. Um, like I see the universe is consisting of all of these possible methods of mind, alteration, including things like exercise and getting massages and going to the beach, going, you know, skiing going on, jet skis, all these things

Speaker 1 (14:28): I suspended in circles. Like we are designed to seek out, uh, changes in consciousness, right?

Speaker 2 (14:36): Yeah. We're we evolved to do that. And so it just turns out that alcohol is a pretty suboptimal method for doing it. And sometimes people discover that, uh, and I'm not encouraging someone who's two weeks off of alcohol with hard, with a hard fought victory right now that they're working on to go back and drink. It takes months, potentially years to rewire your brain. But it's something it's worth knowing that you don't need to be terrified or live with a phobia of alcohol for the rest of your life.

Speaker 1 (15:06): I think that fear also comes from the misunderstanding. A lot of people don't really understand why they drank and they think they don't have control over their hands. I deal with this a lot with, uh, binge eaters too. They, they don't realize, I know it sounds super silly, but they don't understand. They have control over their hands. And so they walk around in fear all the time. And I'm like, you have control over what you put in your mouth, like a hundred percent control, no one will ever make you ingest anything you don't want to. And so that, that allows like the anxiety to come down a notch for my clients too.

Speaker 2 (15:43): I don't know a huge amount about eating disorders. I assume that there's some neurological overlap with things like alcohol addiction. And I've, I developed a lot of compassion for people that I think I previously would have written off as careless or reckless or stupid based on a snapshot assessment of their appearance until I went through my, uh, issue with alcohol. And I mean, I, myself ended up gaining a lot of weight when I was drinking. Some people tend to lose weight and they just eat less. And, you know, they stop absorbing nutrients. I'm sure I wasn't absorbing nutrients, but I would, I mean, I would eat disgusting things when I was drinking. So I just tended to gain weight and they would make me inactive. My workout sucked. So I was like, I feel like maybe, like, I remember thinking maybe I had like a food problem at the same time. Cause when I would drink, I would want to eat the worst stuff. And I was like, maybe all of this is interrelated.

Speaker 1 (16:39): Yeah. Uh, so when you drink alcohol, it reduces leptin for up to 48 hours after. So that's why people tend to eat junk food the entire time. Right. And if you're drinking all the time, then you're left in suppressed. Um, same thing happens with eating disorders like anorexia, uh, leptin is also suppressed and that's what causes them to keep doing the behaviors that they're doing. It's all, uh, it's all, compulsion's, that's what it is. That's how I see eating disorders and drinking. It's all compulsive behaviors. And so neurochemically like you have to fix that because rigidity is often corrected by like glutamine balances, blood sugar, low blood sugar, you become very rigid. If you have a bunch of like catacholamines in your prefrontal cortex, um, that allow alanine, they find that people that are addicted to alcohol have lower levels of dopamine. Right. And so that helps with them. Uh bulemia same thing, lower levels of dopamine. So it's all, it's all interconnected. It's just whatever that person like chose to use to manage their anxiety, alcohol or needed disorder. It's funny other substance

Speaker 2 (17:53): Dopamine is often framed at least by implication as the culprit and addiction. And that's the bad thing that we're chasing because the alcohol is causing an artificial release of dopamine and that's why we hit and we do it. Um, and you know, say cocaine, dopamine, like almost synonymous. It's like the problem isn't necessarily though the fact that you have dopamine, is it?

Speaker 1 (18:14): No, uh, dopamine is the motivational chemical. So it's more of seeking out an activity. So a lot of people that use like cocaine or, uh, harder drugs, um, it's the ritual of going and getting it. And that is the dopamine hit. It's not even necessarily the use of the drug that heightens their dopamine. It's the behavior of going and getting it and accomplishing it.

Speaker 2 (18:43): I actually have had some clients who even after quitting drinking would continue some bizarre rituals that they would do. Some of which were not good. Um, you know, shoplifting being one of them, even after quitting drinking and like, they would be flabbergasted at this. It was like, what is going on? Why am I doing that? And so the way I understood it was that there's still this dopamine list, neural pathway associated with the process of what you were doing. And we have to extinguish that by crowding it out. Like you need to go to spin class when you would be shoplifting or whatever it was that you were doing. There was not good. Um, you know, going on. Yeah,

Speaker 1 (19:22): Nope. A mean engaging behavior at that time is what I usually have my clients do too. I'm sorry. Can you repeat another, like dopamine engaging behavior, motivational behavior in plates of that and crowding it out like you were saying,

Speaker 2 (19:36): Right. Yeah. I was going to say like, going on like Tinder dates and we used to get drunk, but like now you're going on five of them in a day instead of, you know, um, instead of a one and then drinking. Um, so yeah, it's very odd how the brain works, but dopamine is not a bad thing and it's a good thing. We want to probably increase levels of these things and just make sure that people are able to utilize them in conjunction with activities that are good for them in the longterm.

Speaker 1 (20:01): Yeah. Everything is like a cost benefit. And also, and, um, I, I always say that I'm wired in a way to be addicted to like anything. So I better choose my addictions very carefully. Right. And so when I quit drinking and doing any kind of substances, what I started doing is I started writing. Right. And that is, that hits my dopamine pathway, just as good as anything else because I get a reward from figuring stuff out and publishing it. And

Speaker 2 (20:35): I write pen to paper every morning. Um, when I read them and I, I get a, that's like my first buzz of the day. And, um, it actually, I didn't always do that. I did when I was in a horrible place in detox because I had nothing else to do. And I figured I should. It felt obligatory, but I figured I want to look back at this bizarre time of my life. And then after reading the miracle morning, which Matt Finch had suggested to me after a year or so ago, I started getting back into it. And it's one of the best things that, that I've done. It's like, I love to write. And now I write in a kind of weird masculine way where it at least starts out as like lists. And like, everything's very like direct and to the point, but if I get in the right state, things start to flow and I might get a paragraph here and there, I guess everyone has their own style, but writing can certainly be a dopamine bruise.

Speaker 2 (21:29): But I tell some, some clients will say, you know, I know I'm supposed to rewire my brain so that I like to write in my journal, but I just don't like doing it that much. And I can't. And they'll say, in fact, I don't like doing anything right now, the only thing I want to do is drink. And so sometimes to get people to understand that that's a, an illusion, you know, we tend to view reality through the lens of a biochemistry at any given moment. And so we have this neural pathway associated with drinking with probably a series of them. And they're all like, you know, firing, like, what about us? What about us? And it's, it's overshadowing everything else.

Speaker 1 (22:03): Yeah. Uh, and especially with binge drinkers, they tend to have had higher lows and highs. Right. And so it takes a while to get accustomed, to not like seeking out something that is giving you that high of a high, right. You need to resensitize your brain. So to speak.

Speaker 2 (22:24): I found when I resensitized my brain, what I expect to feel was, was a kind of bleak existence where I just were things weren't that much fun and things just didn't bother me. So I figured from what I had heard from people who did the traditional long-term 12 step model, was that like, yeah, life's not as exciting as it was when I drank, but I also don't have panic attacks every day. So I was like, I don't know if that's a good trade off or not. Um, but so I think because of the biochemical repair, like that sounded depressing to me, but because of the biochemical repair and getting into fitness, I found that actually, when you were at least when I re sensitized to my brain, my best highs are honestly better than when I was chasing an alcohol high. My baseline then was so low.

Speaker 2 (23:11): It's like my baseline had been reset low and I didn't know it. So now I can get a much better hide having a conversation with my good friend from college when I'm in that car, you know, and I'm laughing and it's way more fun. I feel physically better than I did when I was drinking a bottle of wine, like trying desperately to feel that way. I couldn't do it. Um, and now I also, but I also don't have, I mean, obviously I'm not having panic attacks every day, so that's good. But my highs are at least as high as they were. They just make more sense.

Speaker 1 (23:41): Exactly. And I think all of us are like unique on what does it. I definitely have to have exercise in there cause mine, I have endorphin issues for sure. Um, we talked about that before I'm on low dose naltrexone, but I have to like go do an intense workout when I feel that like super low. Right. Because I need the contrast of a high

Speaker 2 (24:04): And

Speaker 1 (24:06): It's way better than anything you can get from a substance though. Right. When you go and do an intense workout, like that kind of high is like way better. And then you don't feel like crop too, right?

Speaker 2 (24:17): Yeah. The feeling after like an hour of hot yoga in 105 degree room, or for me like my MMA sessions when someone's basically trying to kill me for however long. Yeah. Just the primal feeling of like I'm alive. Like that's kind of what I wanted from alcohol. I never really got it. Obviously I got some highs from alcohol, but they would progressively dwindle as my brain chemistry deteriorated. And I became actually deficient in the very neuro-transmitters that I was trying to artificially release. But now with a balance, it's like, I know which things work for me. And it's, it's, it's kind of effortless to get a series of highs throughout the day. It's like I have ups and then flats throughout the day, but the flats aren't bad. It's just like, you need to recoup, you can't have constant highs all the time, but I don't really have that many downs anymore. It's kind of amazing.

Speaker 1 (25:08): I think a lot of the people that do like the 12 step model, I don't, I'm not like bagging on it or anything because I think it does help people. But I think a lot of that is the sense of powerlessness too. Even if like there, a lot of them are probably inflamed too. So that's probably what leads to pleasure deficits. Right. But even if they're not,

Speaker 2 (25:30): Yeah.

Speaker 1 (25:30): Like just from eating crap food and being overweight. Right. Um, but even if they're not, I think the sense of powerlessness and that you have no control over your life and your hands gives a lot of people like underlying anxiety where they can't feel really good because they're always in a state of like, I need to be hypervigilant of everything around me and control my environment and which that's no way to live.

Speaker 2 (25:57): Yeah. I think there are a lot of self fulfilling prophecies and beliefs that we can engrain that become self fulfilling prophecies, the powerlessness being one of them. And I, I think for me, it could have been, if I had allowed myself to believe that long-term, it could have become an excuse for not, not doing things that I should have done or, or, you know, choosing not to take risks or choosing not to, uh, my best self and live fully. Yeah.

Speaker 1 (26:29): I play, that's what I've played out for me too. That's just not my personality. I can't do that.

Speaker 2 (26:35): [inaudible], it's also a potentially self fulfilling prophecy. If you think that you're going to be addicted to something though anything. Right. And that's something that you probably thought of before. Cause I, I have said that before. I remember for about a year after I quit drinking, I would tell people I had an annex brain and that was a bit extreme. Like I definitely, I probably, if I don't now than I've definitely had endorphin issues, I, I like you need to go to the gym if I want to feel like fantastic. It's hard for me. If I haven't worked out in like four or five days, which doesn't happen often, but I think it happened at some point during the pandemic when my gym was closed and I'd ordered a weight fast and it was raining and I just didn't want to go outside. Yeah. And I was, I was feeling kind of blocked and not bad, but definitely blah, without the exercise. So yeah, I'm sure I'm dependent to some degree on the exercise, but I no longer say that I have an addict brand because no, I'm not accusing you of saying that either. But when I did say that, I feel like it, there was a risk of that being a long-term a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Speaker 1 (27:40): Yeah. And then you think you will become addicted to anything you take in and you don't listen to your body. Right? Uh, well, they've never isolated, any kind of gene that shows any addictive, like personality. Like, so, uh, what, I mean a lot when I say that it's just like a inference to like who I am. Like, I just I'm extra with everything. Right, right. Yeah. Everything that I like, like I'm not worried about, but

Speaker 2 (28:11): I had someone tell me that I was an extremist, not ideologically, we weren't talking about politics, but I was like, yeah, I think that makes sense. Like there are certain there I have funny little extreme habits. Like I tend to, um, I like to keep a 10 hour eating window if I can sometimes eat sometimes six. And if I go to a restaurant it's not uncommon for me to order like two or three entrees. And then the waiter or waitress will say, you know, there's no way you can eat that. And I'll say, watch me. It's like, I, I guess that's an extreme ism for some people.

Speaker 1 (28:48): Well, yeah. That's my personality too. Like it's the same, I'm sure you're the same way in the gym too. Like when you're lifting, like you just push yourself to your limits, even without someone standing there, like trying to micromanage you. Yeah. For sure. Yeah. That's how I,

Speaker 2 (29:04): I think that's a good trait though. I'm happy I have that. Um, and I'm going to have to, some people, don't the issue of genetics is interesting though, because I, I mean I've long puzzled over this. I feel like, and I'm not a geneticist, but there's never been a gene that determines anything. It's a collection of genes that until we probably have some ridiculous AI algorithm that en that has mapped the genome and everything else and, you know, its relation to neurochemistry and probably the, you know, if you want to do it like a full analysis, you need to know what our environment, uh, all of the inputs from our emotions, what we're eating, what the air quality is, what chemicals we breathe in through our life. If you could map out all of that, I bet you could say that because you have XYZ and a million other genes, or maybe a hundred other or a thousand other genes, you have a slightly higher incidence of being addicted to something. I bet that does exist, but there is no one gene that determines anything as far as I know.

Speaker 1 (30:06): Yeah. I think that that's definitely the case. I think we'll never have the ability to test every variable. Um, so that's why I don't take a deterministic like viewpoint on addiction. So is because I'm like, there's people that have had a whole host of like variables input into the same system that you're working with and they just decided one day they were going to stop. So if that doesn't tell you that you have some kind of freewill around your addiction, like, I dunno, what does, I know it doesn't feel that way because I, I mean, I've been there. It does not feel that you have free will, but you do.

Speaker 2 (30:46): I mean, I often say I quit hundreds of times and failed to quit. Cause I would go back to the alcohol, but the last time I quit, it worked. So I must have freewill cause it was my idea to quit. But my freewill had, had been insufficient for the prior. We'll say 150 attempts at quitting and I'm a pretty strong-willed person, you know? And I'm someone who will, you know, be self motivated, go to the gym, do 10 sets of 10 for squats or whatever. It's seventy-five percent of my max and you know, just tough it out. But I was whatever sliver of freewill I had back then was not, not strong enough. And I think that's because I had no idea of how to fix myself biochemically. I didn't even know that I should, I didn't know what was going on, biochemically. So many people just conclude that there who are actually strong-willed people conclude that they're bad people and they're weak. And really it's just, all they need is a blueprint for biochemical repair and psychological repair. And of course it all. I like to talk about the bio psycho social spiritual model, and all of these things are kind of intertwined, but social strategies and, and spiritual, uh, development, these things are important too. And all of it, it's, it's all layered together into the same thing. It's you can have a transformation, even if you failed 150 or 1,050 times in the past.

Speaker 1 (32:11): And I, I think that addicts tend to have more, uh, determination than most people because how many people will get drunk and deal with those hangovers every day and then go get their drug of choice. Again, like that takes a lot of determination to put your body through that.

Speaker 2 (32:29): I like to say I'm lazy. I'm too lazy to, to be a heavy drinker anymore because it was so hard to get myself like literally buttoning my shirt in the morning with a cold sweat and like trying my bloated Shannon. It was always right here. The alcohol would cause blurted shin and I feel unattractive and horrible and my hands are shaking trying to get that button. And of course I was going to be 15 minutes late if I was lucky trying to get the button to actually go into the hole was infinitely harder than starting a website. And having it rank on page one in Google.

Speaker 1 (33:03): Exactly. It takes a lot, but you're right. I think people will position it well.

Speaker 2 (33:12): Yeah. P and people who go through that just tend to have a lot of willpower it's just untapped and what they haven't given themselves is a viable strategy for harnessing their willpower.

Speaker 1 (33:24): Yeah. And I think a lot of times, uh, the reason why we, it takes so many times to quit, right. And we say, we're never going to do it again is because we haven't worked out all the reasons. We still think we hold onto some sliver of hope that we're going to be able to learn how to do it. Right. Right. And we have to get to a point where we're like, okay, we're never going to be able to learn how to do it just so, or we would have already been there. Right. We wouldn't be dealing with this issue.

Speaker 2 (33:53): Exactly. Yeah. I think as long as there is an illusion that alcohol needs to be part of your daily routine at the very least. Right. Because for some people it's too much to say, you need to quit this forever for me. Like that would have been too much, even though I, my whole life had been ruined by it. I didn't really want to think about that. I got to the point where alcohol had been totally pushed off my priority list. And I was like, all right, I'll never drink again. I don't care. But I think some people, you know, they, they don't want to think about that, but you can say, look, it makes sense. Doesn't it? That alcohol is not going to be a normal part of your daily routine because if it is then you're probably gonna have a problem like drinking every day. Now they just revise the guidelines for safe drinking. I think it's down to, like, they used to tell men they could have two, is it two drinks a day or three? They decreased it to like one or two. Um, I don't know if there was some, some PC issue there because I think the implication was for women. It's like zero. Um, but basically alcohol is bad or is it one for women?

Speaker 1 (34:55): Zero. Um, and so I'm writing an ebook on cancer too right now. Cause I had cancer. Um, and I go into all the research on cancer and alcohol, right. And even one drink and moderate, moderate drinking, like a couple units a week for a woman increases her breast cancer risk by 30%. That's like very moderate drinking. Like how many people actually only have one or two glasses a week? Not very many. We are risk goes up. The more you drink. Yeah.

Speaker 2 (35:28): Yeah. And so I think that if you can, if someone can focus on trying to reorder their daily routine, such that alcohol has no in it, then, I mean, life is just a summation of days. So if you keep living your, your best possible days and alcohol is not part of the daily routine because it really shouldn't be, uh, then at some point you stopped, you literally stopped caring. You're like, Oh, well, good riddance. You know, and that's kinda the only thought you have

Speaker 3 (35:57): Love that.

Speaker 2 (35:58): Well, Brenda, we could talk for hours and I'm sure we will. Um, but I really appreciate you coming on the podcast. I think.

Speaker 3 (36:05): Thank you for having me.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply